Background of the Story

After the births of Dhṛtarāṣṭra, Pāṇḍu, and Vidura, the question of the heir to the throne of Hastināpura became a matter of concern to the elders of the Kuru race. The throne, vacant since the death of Vichitravīrya, required a ruler who could uphold dharma and preserve the might of the lineage. 1

The Story

Though Dhṛtarāṣṭra was the eldest, his blindness disqualified him from royal duties that demanded vision and leadership. Vidura, wise and spotless in conduct, was passed over because he was born to a maidservant and thus considered inferior for enthronement by the law of the age. The eyes of the court naturally turned to Pāṇḍu, whose learning, valour, and humility made him the ideal choice.

At the insistence of Bhīṣma, and with the consent of elders like Satyavathi, Pāṇḍu was crowned king of Hastināpura. The ceremonies filled the city with rejoicing. The royal banners fluttered high, and conches sounded across the Yamunā.

As king, Pāṇḍu upheld justice, subdued neighbouring realms, and brought prosperity to his people. His rule was marked by discipline, learning, and compassion. Yet destiny, unseen by all, was preparing another course for him-one that would lead from the palace to the forest, from the sound of the drum to the silence of penance.

The hunting of the Deer

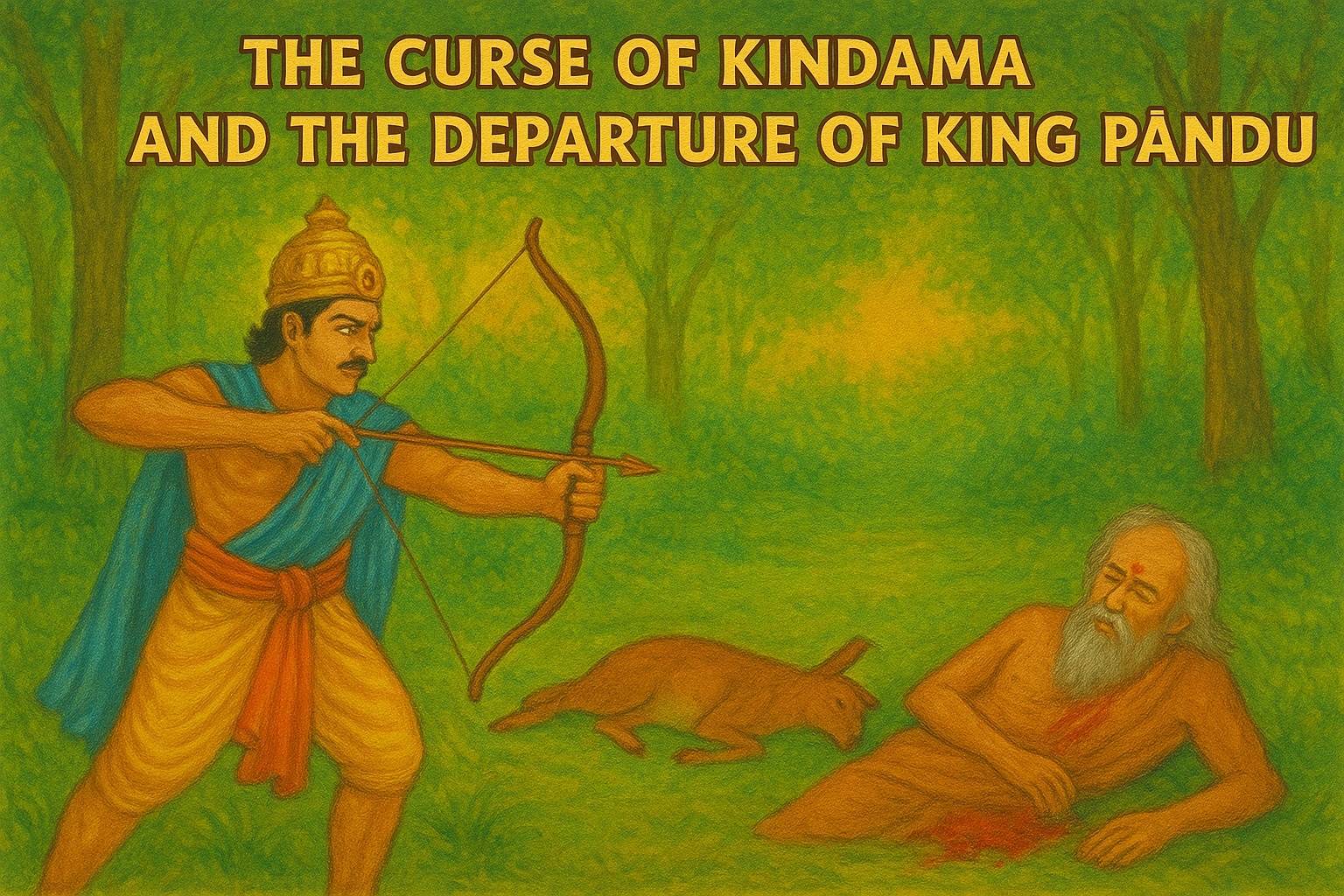

The sound of hunting horns echoed through the forest of the Kurus. King Pāṇḍu, radiant and strong, pursued the royal sport that was both exercise and royal duty. Around him galloped the sons of nobles, while his arrows brought down lions, tigers, and wild boars. The forest trembled under the king’s mastery.

As the chase thinned, Pāṇḍu wandered alone, eager to test his skill. There, among flowering creepers, he saw two deer locked in embrace. Their movements were slow, absorbed in love. The sight stirred the hunter’s instinct.

“This pair moves not for fear of man,” he thought. “They have lost all caution. Let my arrow strike true.”

He fitted the shaft, drew the bowstring, and released. The iron point found its mark.

Instantly there rose from the glade a cry unlike any he had heard -half human, half divine. The deer fell, and before his eyes assumed the form of an aged ascetic, Kindama Mahārṣi, with his wife beside him. Their bodies bled, but their faces glowed with spiritual radiance.

The sage spoke, voice trembling yet stern: “O King, even among beasts, who are moved by desire, no creature strikes another in such a moment. Yet you, born of noble blood, have slayed a hermit in the act of union. In your passion for the hunt, you have sinned against life and love alike.”

Pāṇḍu’s Justification

Pāṇḍu stood aghast, but his reasoning as a kṣatriya remained firm. “Revered one,” he said, “I roam these woods by the law of kings, protecting my people and subduing beasts of prey. Whoever wears the form of a forest animal is by that very form the object of the hunter’s arrow. How could I know that you were a sage disguised as deer? If ignorance is fault, then the world itself is tainted, for none can see the hidden heart of another.”

But Kindama’s anger deepened.

“I don’t object the king’s duty of killing animals. But you should have waited till the completion of my act of love-making. … As you have been cruel unto a couple of opposite sexes, death shall certainly overtake you as soon as you feel the influence of sexual desire.”

As I die in love’s embrace, so you also shall die in love’s embrace.”

Thus declaring, the sage fell dead, his body luminous like fire fading to ash. Pāṇḍu gazed upon him, his confidence dissolving into dread. The shaft that had struck the sage now pierced his own conscience.

Renunciation

Pāṇḍu felt bad at his own misdemeanour and his act of transgressing dharma. He wanted to renounce the kingdom and go for forests for Vānaprastha. He asked his queens Kuntī and Mādrī to go back to Hastinapur, but they wanted to stay with him. They too wanted to lead ascetic life in forests. Pāṇḍu agreed and, accompanied by his wives, went north to the hermitages of the Himalaya. There he lived among sages, clothed in bark, eating fruits and roots, performing sacrifices, and meditating on destiny.

The once-golden monarch now sought purity not through conquest, but through surrender.

Vyāsa’s Teachings on Vanaprastha

In time, the great sage Vyāsa came to his hermitage. Seeing Pāṇḍu’s austerity, he said:

“O King, you have entered the path of Vānaprastha. This is the third stage of man’s life, following youth and household duty. In this way, desire is slowly consumed, and the soul ripens for liberation.

One must dwell in the forest, sustain sacred fires, speak truth, eat little, bear heat and cold alike, and see the same Self in all beings. This is not flight from the world, but mastery over it.”

Pāṇḍu listened with reverence. Yet his heart bore one lingering sorrow-the absence of sons.

The Sages Bound for Brahmaloka

One day, he saw a horde of luminous sages moving northward, their bodies glowing like flame. “Where are you going, revered ones?” he asked.

“To Brahmaloka,” they replied. “Our penance is fulfilled. We are going to Brahmaloka”

“Then take me also!” implored Pāṇḍu. “I too have renounced the world.”

The sages answered gently, “O King, only he who has left behind worthy sons may reach the eternal worlds. For through sons is the line of sacrifice continued, and ancestors sustained. You have no children.”

Their words struck deep. The king sat long in silence beneath a Sal tree.

The Law of Niyoga

At length he turned to Kuntī and spoke gravely:

“My queen, destiny denies me natural fatherhood. Yet dharma offers a righteous path. The ancient practice of Niyoga allows a wife, with her husband’s consent, to obtain a child from a virtuous man for the sake of lineage. The son so born is counted the husband’s own.

This act, performed with purity and prayer, is neither lust nor infidelity-it is sacrifice in another form.”

He cited examples-his own father Vichitravīrya, whose sons were begotten by Vyāsa himself; and older kings who upheld dharma through such means.

“The law declares,” he said:

- It must be done with sacred intent, not desire

- The chosen man must be pure and learned

- The union must occur at the proper season, and only with the husband’s sanction

- Thereafter the woman remains faithful and chaste

Pāṇḍu concluded: “Let us thus fulfil dharma and ensure that our line of the Kuru kings does not end.”

Kuntī’s calm face concealed deep thought. Within her heart she remembered the boon of sage Durvāsas, by which she could summon any god. But her secret she kept. What she answered, and what destiny unfolded, shall be told in the next story.

Points to ponder

The Curse of Kindama – The Ethics of Desire and Ignorance

In Ādi Parva (Ślokas 12-17 of Chapter 117, Gita Press), Pāṇḍu argues from kṣatriya dharma that hunting is no sin when done in ignorance. It is dharma of a king to kill animals and protect people. Yet Vyāsa subtly presents a deeper moral layer: sin may arise not from intent alone, but from timing and blindness of passion also. The act of killing animals when they are satiating the biological urge is morally not acceptable.

Kindama’s curse mirrors karmic symmetry-Pāṇḍu, who killed animals in the act of love, will die when moved by love. The episode thus blends kṣatriya justification with āśrama ethics, showing that dharma’s boundaries shift between worldly duty and ascetic restraint.

The Philosophy of Vānaprastha

Vyāsa’s discourse in Ādi Parva details the ideal of forest life as a gradual detachment. A Vānaprastha:

- withdrawing from possessions and sensual life,

- maintaining fire and ritual duties,

- eating roots and fruits, and

- welcoming all beings equally.

This stage is not denial but discipline-training the mind to live without dependence.

The Dharma of Niyoga

Niyoga-dharma-the begetting of offspring by a chosen righteous man-appears repeatedly in ancient texts:

- Veda Vyāsa fathered Dhṛtarāṣṭra, Pāṇḍu, and Vidura by Niyoga (Ādi Parva 104–105).

- Manu Smṛti (IX.59–68) and Śānti Parva (Ch. 320) define its limits: consent, purity, and intent for progeny, not pleasure.

- It was accepted when lineage or social order was at stake, and condemned if done from lust or secrecy.

Vyāsa’s inclusion of this dialogue in Pāṇḍu’s story is deliberate: it situates moral law (dharma) above personal purity or passion. Top of Form

One thing which we should not forget from this story is that

There was no formal abdication of the power in favour of Dhṛtarāṣṭra by Pāṇḍu. Since Pāṇḍu’s sons (the Pāṇḍavas) were born of him (through niyoga), the question of who is the rightful heir later becomes central to the succession dispute that fuels the Kuru war.

So - from a dharmaśāstric and narrative perspective:

- Dhṛtarāṣṭra only acted as regent or caretaker.

- Pāṇḍu remained the legitimate king in name, though retired.

- After Pāṇḍu’s death, his sons, being the legitimate heirs, had a claim to the throne-stronger than that of Dhṛtarāṣṭra’s sons (the Kauravas).

This is why Bhīṣma, Vidura, and even Dhṛtarāṣṭra himself at times admit that Yudhiṣṭhira is the rightful heir.

Questions

- ‘One may be legally right, but morally wrong’ – what does it mean? Give some examples from your own understanding of the world.

- What are the four āśramas specified in our Dharma?

- Why are many Hindus, including the traditionalist have broadly neglected Vānaprastha and Samnyasa? Have people forgotten the principles of renunciation and meditation?

- Do you feel that ancient Bharat was more liberal in the aspect of family life compared to present days? Justify.

This Story is taken from Adiparva of Mahabharata written by sage Vedavyasa ↩︎