Background of the story

Vysampayana was narrating the story of the birth of Dhritarashtra, Pāṇḍu and Vidura to the king Janamejaya. He told Janamejaya that Yama Dharmaraja was born to a Dasi (servant maid) of Ambika and he was Vidura. Upon the request of Janamejaya, he started narrating the story of ‘Lord Yama and a sage माण्डव्य - Māṇḍavya’. 1

Story of Māṇḍavya

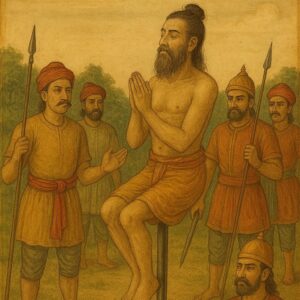

Māṇḍavya was a sage and one day he was sitting beneath a tree in his Ashram. When he was in deep meditation, a few thieves being chased by the soldiers, entered into his Ashram and hid inside. The sage did not observe what was happening. The soldiers questioned the sage as to whether he had seen the thieves running there. The sage did not answer as he was in deep meditation. The soldiers searched inside and found the thieves as well as the stolen wealth of the thieves. They tied all the thieves and also the sage and presented them before the king. The king, without proper enquiry, imposed ‘Soola Danda’ (death sentence by thrusting over a raised trident) to all the people. The soldiers did what was ordered by the king and they felt that he was dead.

Māṇḍavya was such a great Rishi that he continued doing penance in spite of the physical suffering. Pain is to the body and not to the soul. The people in and around were surprised to see the great sage surviving the pain of the trident and still pursuing the penance. For anybody’s query he used to reply that no one was responsible for his suffering.

A few days later the king came to know through his soldiers that the sage was surviving the heavy odds. The king rushed to the spot and ensured the sage was safely grounded from the trident. Upon his orders the soldiers tried to remove the trident but in vain. Then they cut off the trident to certain point but the pointed edge was struck to his body only. The king profusely apologized and the sage graciously condoned his sin. Māṇḍavya began wandering with the trident edge and was meditating continuously. He was famously called and eulogized by all as ‘as Āṇī-Māṇḍavya (āṇī = iron peg).

Question to Yama

One day Māṇḍavya, with his spiritual vision, went to Yama (Dharma-rāja), the Lord of Justice, and asked:

“O Lord Dharma! For what fault of mine was I given such a cruel punishment of impalement?”

Yama’s Reasoning

The God replied, ‘When you were in your childhood, while playing, you had pierced a sharp darbha (kusa grass in Sanskrit) grass into the tails of the locusts. So, I have imposed this punishment upon you.

स्वल्पमेव यथा दत्तं दानं बहु गुणं भवेत् |

अधर्म एवं विप्रर्षे बहु दुःख फलप्रदः || 2 – Maha Bharatha Adi Parva 107.12.

(Just as small charity results in the merit growing in geometric proportion, a small sin results in agony growing in geometric proportion’)

Māṇḍavya did not agree with the logic and reasoning of the God of Dharma. Any unrighteous act (adharma) done during childhood should not attract punishment as the children act without understanding the nuisances of dharma or adharma. The law, after all, should be ethical and amenable to reason. He cursed the God of Dharma to born as a human Śūdra on earth.

This curse caused Lord Yama to be born as Vidura, the wise minister of Dhritarashtra.

With his power of tapas, Māṇḍavya, ordained that ‘no child below fourteen shall attract sin for juvenile delinquencies’.

आचतुर्दशकाद्वर्षान्नभविष्यति पातकम् |

परतः कुर्वतामेवं दोष एव भविष्यति || 3 – Maha Bharatha Adi Parva 107.17

(No child below fourteen shall attract sin for felony. Only children above fourteen shall attract sin). From then the rule of Māṇḍavya became the dharmic law of the land.

Vysampayana concluded the story. Then Janamejaya wanted to know about Dhritarashtra and Pandu when they attained youth. We shall discuss this aspect in our next story.

Points to ponder

Was Śūdra-janma considered “unworthy” in Mahābhārata times?

The society in Mahabharata times was that of division of people into four varnas based on their traits (guna) and activity (karma).In ancient times, the human nature was categorized into three gunas: Sattva, Rajas, and Tamas, each representing different qualities and tendencies. A Sattvic person embodies purity, knowledge, and harmony, characterized by calmness, contentment, and a focus on selfless service. A Rajasic person is driven by activity, ambition, and desire, often experiencing restlessness, attachment, and a thirst for results. A Tamasic person is characterized by inertia, ignorance, and delusion, exhibiting laziness, confusion, and a tendency towards negativity. Combination of these gunas in different proportions gave raise to four varna system - Brahmin (Satvic), Kshatriya (More of Rajasic and less of Satvik), Vysya (Rajasic and Tamasic in equal proportion) and Sudra (Tamasic).

If we translate to modern terminology, they are like software engineers, Managers, Marketing people and the attenders. Though all are essential to run a system, they are not equal in status.

Māṇḍavya cursed Lord Yama to be born in the last category of social hierarchy.

Varna stratification was frowned at in Mahabharat times, and, if a sudra displays sattvic gunas, he was held in high pedestal - for example, Vidura was the Prime Minister in the court of Hastinapura; Ugrasrava, a Suta, was the chief narrator of Mahabharata to great sages in Nymisaranya; Dharmavyada, a hunter, taught dharmic lessons to Kausika, a Brahmin and the examples are endless.

When Māṇḍavya cursed Lord Yama, it meant that he should born to a lady of Tamasic nature. Since the child exhibited extraordinary intellect, he was treated in high esteem by all the Kauravas, Pandavas and by Dhritarashtra who made him his Prime Minister.

What are the views of Dharmaśāstras on the issue - “Children below 12 not punishable”

This principle - that childhood acts do not incur sin - is echoed in several Dharmaśāstras.- Manusmṛti 8.316

न बालो न वयोवृद्धो न रोगी न च पीडितः ।

अकर्तव्यो हि दण्डस्य दण्ड आचार्य एव हि ॥4

“A child, an old man, one afflicted with disease, or one distressed - should not be punished. Only the teacher (ācārya, meaning a responsible adult) is a fit object of punishment.”

- Yājñavalkya Smṛti 2.305

बालानां दोषकृत्यानि न दोषाय भवन्ति हि।

अप्रमाणज्ञतायुक्ता नास्त्यत्र प्रतिषेधनम् ॥5

(“Faults committed by children are not faults, for they act without knowledge of right measure; therefore, no prohibition (punishment) applies to them.”)

In this story, Māṇḍavya’s rebuttal was not his personal whim - it reflected Dharma Śāstric principle: that before a certain age (variously given as 12 or 16 in texts), children’s actions are not punishable sins.

- Manusmṛti 8.316

A comparison of child punishability and jurisprudence in India vis-à-vis western civilizations.

Ancient Indian jurisprudence was strikingly progressive, seeing children as incapable of crime until maturity and emphasizing correction, not punishment.Rome came closest in the West with its tiered system, but later medieval Europe regressed into harsh punitive systems even for children. Enlightenment philosophers (Locke, Rousseau) emphasized childhood as a special stage needing education, not punishment. Rousseau’s Émile (1762) transformed the idea of childhood in Europe. 19th century: Industrial Revolution exposed child labour abuses; and reformers began advocating child protection laws. Juvenile courts emerged in the U.S. (Chicago, 1899).

Children’s rights in the modern sense (as independent rights-holders, not just dependents) emerged in the West only in the 20th century, whereas India’s dharmic view always placed a protective framework around children, though without using the “rights” language.

Ancient Indian jurisprudence - how dharma was defined and accepted across Bhāratavarṣa even before there were centralized legislative structures?

In this story we see Māṇḍavya setting a rule - ‘No child below fourteen shall attract sin for felony’. In the aftermath of the great Mahabharata war Yudhishtir says- “No woman can keep a secret in her heart.” Similarly, Maharshi Svetaketu6, on seeing his mother being grabbed by an old man, sets a rule- “licentious behavior of women is prohibited”.In all these cases, the rules prescribed at some corner of the country had become dharmic laws across the length and breadth of the country, and all were following them scrupulously. We should understand that in ancient society dating back to five thousand years, there was neither social media nor proper communication channels. Then how did people follow the rules?

It is believed that the utterances of great sages had become part of Ṛta (cosmic order) because:

Rshis were regarded as ṛta-sākṣins (seers of cosmic law).

Their utterances, when done in tapas-born authority, were seen as manifestations of Dharma itself.

Society accepted it not just out of fear, but because it was seen as an insight into divine order.

Thus, such rulings became binding customary law (ācāra-dharma).

How could such a rule, spoken in one place, become valid everywhere?

Key reasons:

Authority of Ṛishis: In ancient India, sages were above kings in moral authority. Even kings like Daśaratha or Yudhiṣṭhira bowed to sages. If a Ṛishi spoke, the world believed Brahman himself had revealed a truth.

Oral transmission: Epics, Purāṇas, and Smṛtis were taught in gurukulas across the land. Thus, when a new “law” was set by a great sage, it spread quickly through śruti-smṛti tradition.

Pan-Indian respect for Dharma: There was no single empire covering all India for long stretches, but Dharma was universal glue. A law spoken by a sage was not “local custom” but “eternal dharma.”

Smṛti codification: Over time, Manu Smṛti, Yājñavalkya Smṛti, etc., absorbed many such rules.

Ancient society developed debating climate in the centres of knowledge and scholars used to mingle for discussions and debates. This system helped in spreading Dharmic rules set by the Rishis.

Contrast with King-made Laws

Kings issued rajya-śāsana (royal edicts), but these were local and temporary.

Ṛishis’ declarations were dharma-śāsana (moral laws), believed to be eternal and valid everywhere.

Dharma was thought to be superior even to the king. That is why in Mahābhārata it is said: “धर्मस्य तत्त्वं निहितं गुहायाम्, महाजनो येन गतः स पन्थाः”7 (“The truth of Dharma lies hidden in the cave; the path trodden by the great ones is the way to follow.”)

So, in the absence of written codes, India had a pan-Indic dharma culture sustained by:

- Shared Vedic heritage.

- Reverence to Maharshis and Itihāsas.

- Repetition through oral tradition.

- Acceptance by kings themselves, who saw themselves as upholders of dharma, not makers of dharma.

Questions

- Do you agree that law is the codification of ethics and morals?

- Can a law sustain against the principles of Dharma?

- Who has to take the responsibility of adharma being practiced by children below fourteen years?

- Can a meritorious person prescribe law for the general populace as Māṇḍavya did in Maha Bharata?

This story is written by sage Vedavyasa in Adi Parva of Mahabharata. ↩︎

svalpameva yathā dattaṃ dānaṃ bahu guṇaṃ bhavet |

adharma evaṃ viprarṣe bahu duḥkha phalapradaḥ || – Maha Bharatha Adi Parva 107.12. ↩︎ācaturdaśakādvarṣānnabhaviṣyati pātakam |

parataḥ kurvatāmevaṃ doṣa eva bhaviṣyati || – Maha Bharatha Adi Parva 107.17 ↩︎na bālo na vayovṛddho na rogī na ca pīḍitaḥ |

akartavyo hi daṇḍasya daṇḍa ācārya eva hi || ↩︎bālānāṃ doṣakṛtyāni na doṣāya bhavanti hi |

apramāṇajñatāyuktā nāstyatra pratiṣedhanam || ↩︎Maharshi Svetaketu (son of Uddālaka Āruṇi).

Story:

Svetaketu once saw his mother being taken away by another man under the rule of “open marriage” (pre-Niyoga type custom). Enraged, he declared:

स्त्रीणां स्वतन्त्रता नास्ति मातुर्दृष्ट्वा व्यतिक्रमम् |

प्रज्ञया चोदितः शिष्यः स्वयं धर्ममकल्पयत् ||

strīṇāṃ svatantratā nāsti māturdṛṣṭvā vyatikramam |

prajñayā coditaḥ śiṣyaḥ svayaṃ dharmamakalpayat ||

(“Seeing the transgression of his mother, Śvetaketu declared: henceforth women shall not have liberty (to go with other men). Like that he established a dharmic rule”) ↩︎“dharmasya tattvaṃ nihitaṃ guhāyām, mahājano yena gataḥ sa panthāḥ” ↩︎