Saunaka Maharshi was a kulapati (currently, the word is loosely translated as the Chancellor of a University) and he was having more than ten thousand students in his āśramaṃ at Naimiśāraṇya. Once upon a time, Saunaka Maharshi was performing Satrayāga in the vicinity of his āśramaṃ with the help of all his disciples. Satrayāga was of twelve years long duration and all the rishis were committed to perform it with all sincerity and zeal.

Ugrasrava, the son of Romaharshana was a sūta, but highly proficient in narrating tales of all purāṇās and itihāsās. He was physically present in the court of king Janamejaya when sage Vaiśaṃpāyana narrated the story of Mahabharata to the king upon the instructions of Vedavyasa. He was searching for a receptible audience that can listen to his words. Upon seeing a congregation of ten thousand students of Saunaka at Naimiśāraṇya, he was thrilled and reached them.

The students of Saunaka received him very well and they were eager to listen the story of Kauravas and Pandavas from Ugrasava. By that time, Saunaka arrived at the spot and greeted Ugrasrava. He enquired about his yogakshema and asked the reason for his arrival to Naimiśāraṇya.

Mahabharata – the brainchild of Veda Vyasa

Ugrasrava was happy and he started telling. ‘I have come from the court of King Janamejaya who was performing the Sarpayāga (a yāga conducted to annihilate the snakes) and I heard the entire story of the kings of Kuru clan from Vaiśaṃpāyana, the direct disciple of Vedavyasa. Before answering any of your questions I wish to narrate the brief background of Mahabharata’. The rishis were happy, and they enthusiastically asked him to narrate the brief account of Mahabharata.

Ugrasrava started telling. ‘Oh Rishis, Mahabharata is the largest ever known story – both in vastness and richness (महत्वात् भारवत्वात् इति भारतं). Sitting in the lap of Himalayas, the sage Vyasa perceived all the events of Kurus from his intellect-eye (ज्ञान नेत्र) and conceived the storyline. He saw in this story the essence of Vedas, vedāngās and purāṇās. He also saw vividly the dharma, Artha, kama & Moksha which are essential objectives of mankind. He also visualised geographic entities such as rivers, mountains, lakes, and oceans; forests, janapadas, and the people of different regions. He perceived the philosophy, logic, psychology, music, justice, jurisprudence, laws, morals, ethics and the very origin of earth, cosmos, and the origin of galaxies. He saw the births, deaths, worries, and fears that haunt the mankind. He thought that it would be prudent to present the Mahabharat itihās to the populace who could not directly understand the vedas and Upanishads. He wanted to use the text of Mahabharata as a pretext to covey the dictums present in vedas’.

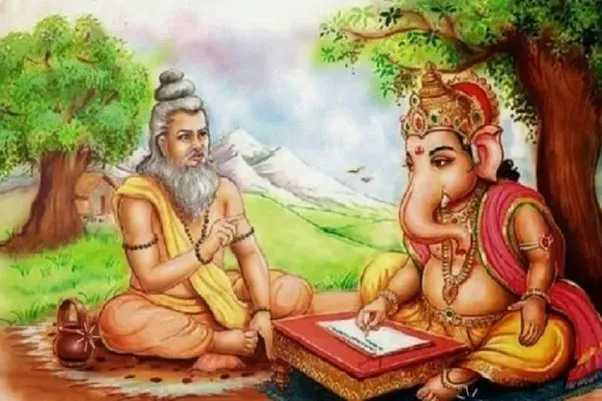

Vyasa, the author and Ganesha, the writer

‘But who would write it?’ Vedavyasa invited Brahmā to his place and sought his help in arranging a writer who can match his speed of articulation. Brahmā suggested to take the help of Ganesha in his endeavour.

When Ganesha arrived at Himalayas, Vedavyasa sought his help in writing the book of Mahabharata. Ganesha thought for a while and said, ‘Yes, I can write while you recite the slokas. But I have a condition. You should keep telling and never allow my pen to stop even for a second’. This is a big challenge, given the speed of Ganesha in writing things. Vedavyasa thought for a while and said, ‘Yes. I can never let your pen stop even for a second. But I too have a condition – you should write only after understanding whatever I recite. You cannot write monotonously’. Ganesha agreed and both sat for about three years to complete the project.

Saunaka was surprised and said, ‘Did Vyasa narrate the story non-stop?’

‘No. To gain time, here and there he recited slokas which can have multiple meanings and not very easy to decipher. Ganesh has to sit back, ponder over the correct meaning and then he was writing. By that time, Vedavyasa could conceive a few dozen slokas to keep engage the attention of Ganesha. In this way Vyasa recited around eight thousand eight hundred difficult slokas which are popularly known as ‘Grandh Grandhi’ (Grandhi means a knot)’.

They, thus, completed compiling Mahabharata in around three years’ time.

Mahabharata – how it spread?

Janamejaya was a great grandson of Arjuna (Abhimanyu was the son of Arjuna. His son was Parīkṣit and Parīkṣit’s son was Janamejaya). When Janamejaya ascended the throne, he was minor boy, and he was not aware of the story of his great grandfathers. He was performing Sarpa yāgaṃ (a sacrifice to annihilate the entire race of snakes). A rishi by name Asthika influenced the king and thus the yāgaṃ came to an end. Vedavyasa came to the court of Janamejaya and upon the request of the later, deputed his disciple Vaiśaṃpāyana to narrate the entire story to the king in his court.

Ugrasrava concluded his narration and said to Saunaka, ‘Hi Rishi! I was present in the court of Janamejaya when the Mahabharata narration took place. With all supporting upākhyānās (stories not directly connected main storyline) the Mahabharata is of one lakh slokas. Now I can narrate the whole story which I had heard from Vaiśaṃpāyana.

The rishis were happy and sat around the sūta for hearing Mahabharata.

Points to Ponder

- The purpose of writing Mahabharata by Vedavyasa is to spread the message of Vedas to common people (वेदोपबृंहणार्थाय- vedopabṛṃhaṇārthāya). Vedas, it is said, are like commandments of a king – like ‘satyam vada’, ‘dharmam chara’ etc. The depth of the dictums may be understood by the enlightened persons. To make them understand for common people it is necessary to weave a story, for example, the story of Harischandra, Nala, or Sibi. Mahabharata and its stories are case studies to understand the nuances of dharma. Hence it is called Panchama Veda or fifth Veda (the other four being Rig Veda, Yajur Veda, Sama Veda & Adharvana Veda).

- Mahabharata has been narrated by Ugrasrava, a sūta by caste and it was listened by a rishi and his ten thousand students. A sūta is from the progeny of chariot makers. In Mahabharata times the intellect and the wisdom of the person decided his social status and there was no hesitation for rishis to listen to his narrative. It was an egalitarian society.

- The Kulapati concept was very prominent in Bharat in ancient times. It is like a present-day university where the pupils congregate to study different fields of study. The calling of the present-day vice chancellor as Kulapati is thus an apt translation of the word.

- Mahabharata is a vast book with eighteen Parvas. It is an elaborate narration of all fields of knowledge of its time. Vedavyasa visualised it and pronounced famously – ” यदिहास्ति तदन्यत्र यन्नेहास्ति न तत् क्वचित् “- yadihāsti tadanyatra yannehāsti na tat kvacit”. It means whatever here is there anywhere; and what is not here is nowhere. In Mahabharata we find the famous scripture Bhagavad Gita. We also find Vidura Niti, Vishnu Sahasranama, Yaksha Prasnas, and a vast number of anecdotes depicting raj niti, dharma, ethics and moral principles.